My family has a holiday ritual we’ve all come to look forward to.

Every year, every weekday after Thanksgiving (but before the first week of January), we each head back to work.

There, we exchange reports of what we did for Thanksgiving (“Not much, we just drove down to see my wife’s parents in Macon…how about you, Gina?!”) or what we’re planning for Christmas (“Not much, we’ll probably just drive down to see my parents in Savannah; your folks are in Tampa, right?”)

We pull out our notebooks and fire up our computers.

Then we do absolutely nothing we’re supposed to.

Instead we shop for Christmas gifts. We look up plane tickets to wherever the family has agreed to meet for the holidays. We exchange recipes and party ideas.

We take too many coffee breaks so we can run into our colleagues and talk about how we’re all doing nothing and how no one really wants to be working.

Then we come home, lament all the above, and prep to do it all again the next day.

–

As I type this, I’m listening to my sister-in-law verbalize her calculations on exactly how little work she needs to do today to not piss off her manager while she does what she really wants to do, which is not work right now.

She’s found company in me, who (until I started writing this) was making poor attempts to focus on my deliverables. Deliverables due days before Christmas which is when my other deliverables (see “gifts,” above) are also due.

It’s been almost a year since I was in an office building, but I can’t imagine the ritual would’ve gone any differently this year than last.

This time last year, there was almost no one at work. Meetings were half-attended or canceled as colleagues skipped town. Clients were unavailable. Decisions were paused because it “probably makes sense to kick this off in the new year.” Personal days trended up.

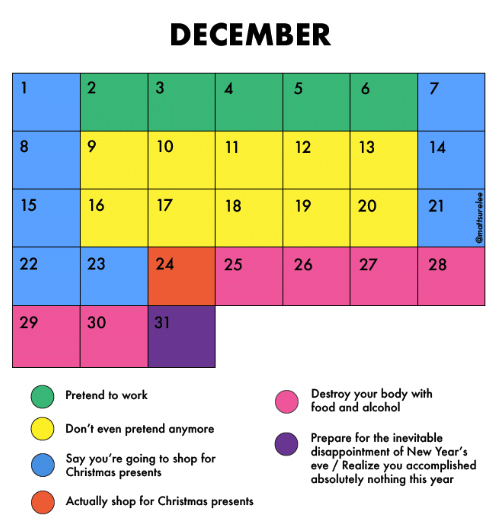

Office gossip shifted from reviews and promotions to Christmas party outfits. All avoided even the suggestion of burden. “Any volunteers for this high-priority step-up opportunity sure to impress the CEO?” On the 22nd of December? No thanks. I’d rather die a middle-manager. Essentially, per Matt Shirley…

It makes sense. December days are short and nights long. It’s Cold, the official sponsor of blankets, fireplaces, and soup everywhere.

Even where it isn’t cold, it’s still December, which means you’ve successfully seen off January, February, and the rest of their annoying siblings.

That’s hundreds of working days, too many meetings, and thousands of phone calls. It’s been failed resolutions and successful self-help courses, all equally exhausting. It’s been dozens of awkward interactions with that one neighbor you don’t like, and too many arguments with your boyfriend.

By December, it’s been a long year.

–

In no year of my life has this been truer than in 2020. I’ll spare you the overused descriptors (“unprecedented et al”), but I’m challenged, even now, to completely process my own feelings about this year.

My family and I were spared the worst of the coronavirus, but three of us tested positive, and it still feels somewhat farcical: my attempts to be effective in meetings and accurate in my submissions while my cousin lay retching and shrinking alone in his apartment; status updates while my sister quarantined herself away from her 1-year-old.

Add to that the suddenness with which White America was forced to acknowledge the perils of simply being black in America, the dangers embodied in the Amys and Dereks waiting around every corner to spring traps on the blacks.

I didn’t march. Of course not. I had meetings and deliverables. And I hated myself for it. That too was exhausting.

–

We should have had December off. We should have taken the time to rest, to balance out the grind of the year with some calm and reflection. We should have prioritized the care and endurance of our people, and granted time off without cost to our PTO banks.

Christmas Day isn’t enough to sleep, laugh, cry, celebrate, seek help for, understand, bury, mourn, document, and recover from the events of the 360-odd days that come before it.

We should have a full week in December, maybe two or even three, to really recuperate. Together. As families and communities. Every year. In a country where voluntary PTO comes with vacation guilt, companies shutting down or giving mandatory time off would literally change lives.

We definitely should’ve taken December off this year. That we didn’t think to, even after everything this year was, says things about us as a society, I think.

It says things about our resilience and adaptability, yes. But there’s a relentlessness to our pursuits, and to our inability to prioritize ourselves for more than two days in a row, which I think is a bit sad.

Not sad just in the David Attenborough we-burned-down-the-forests-for profits way, but sad in the “what will it take to make us rest?” way.

We remind me of Winston Churchill in the back half of Season 1 of The Crown, when the character kept insisting on his country’s greatness and his stamina even as both were in decline.

–

The irony of that particular connection vis-a-vis the US and the UK especially is that other civilized societies do this, annually, somewhere in the year, as ritual.

Basically all of Japan shuts down for Golden Week every April. China does the same later in the year. A safe assumption in Nigeria during the last two weeks of the year is that most companies are closed.

Western Europeans essentially disregard August as a legitimate work period and prioritize vacation with their families. We mock them for it, with that awkward tone of voice that betrays jealousy.

We know they’re better off for it, and that we’re mostly deceiving ourselves. No one at work is actually doing work right now. Productivity at desks from sea to shining sea has likely plummeted. We’re miserable, and we’re all talking about it.

Why not drop the charade and shut it all down? There was a quote in my Daily Calm recently: “Nature often holds up a mirror so we can see more clearly the ongoing processes of growth, renewal, and transformation in our lives.” If Mother Nature sees fit to slow it all down in December and pick things back up in Q1, why can’t we?

–

There are mechanics I haven’t thought through. Would these two to four weeks off be paid time off? If so, how would we pay for it? Would every employee contribute a portion of their pay throughout the year towards this break, like a one-year 401K? What sort of pressure would that put on struggling families? Would companies offer it as an employee perk and fund it through profits?

Who could participate? Continuation of some commercial activity – grocery shopping, dining out, logistics, travel & hospitality – implies that some members of our communities would still be working while others were off.

Would that make this a white-collar, middle-class+ scheme, deprecating the spirit of communal rest and rubbing further salt in the immoral wound that is income inequality in our country today?

Does it even make sense to ask this right after a pandemic has forced companies to shut down for extended periods already?

I don’t know. Maybe. Maybe not. But some societies have at least asked and answered these questions. We could too.

Something to think about for next year, perhaps. In the meantime, you’ll have to excuse me. Need to get back to these deliverables.

Join me next time when we’ll discuss “Your birthday should be an automatic day off.”